Intel caught in pincer movement

It’s between a ROC and a hard place

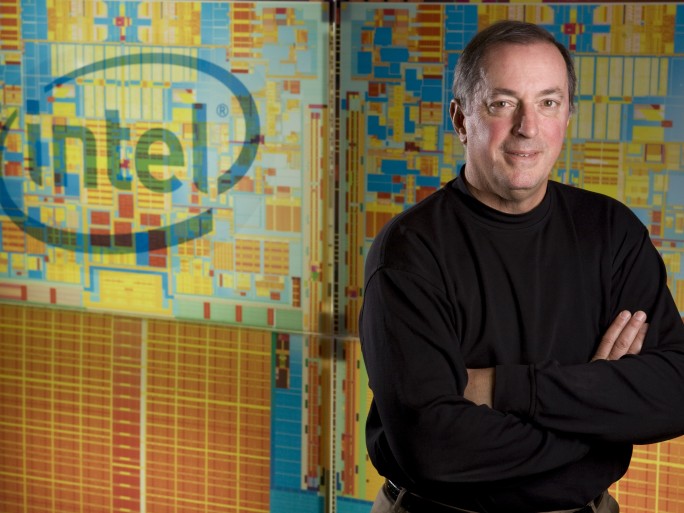

The premature departure of Intel CEO Paul Otellini, earlier this week underlines the fierce pressure the formerly invincible chip giant is under. Otellini will retire from Intel in spring next. British senior executive Sean Maloney is set to retire at the end of January.

While there’s speculation about who will replace Otellini, including former rising star Pat Gelsinger who now works for EMC, sources close to the company told us back in September that there was widespread unease inside Intel about the way it was heading.

According to these sources, Andy Bryant, a member of the board and the former chief financial officer, agreed to defer his retirement to keep an eye on Intel.

It certainly needs keeping an eye on. Despite spending vast sums of money over the last several years on the Atom microprocessor, hoping against hope that it would make headway in the mobile and tablet markets, Intel has only a handful of design wins. Manufacturers of handsets don’t want Intel – and Microsoft for that matter – to gain the kind of dominance they’ve had for years in the X86 market. There’s also a technology argument too. Mobiles based on ARM architecture are more power efficient and also very much cheaper than Atom chips.

Intel has also been caught on the hop by the success of tablet PCs while people seem to be underwhelmed by its latest push into notebooks in the shape of the Ultrabook brand. In these straitened times, people do not want to pay hundreds and hundreds of pounds for a machine which is basically a copy of an Apple Mac.

The chip giant has bet the company on a dual strategy and there are clear indications that it’s not paying off. Every market research company worth its salt is indicating a further decline in sales of X86 machines, the bread and butter that have allowed Microsoft and Intel to ride for years on the gravy train.

Intel has a track record of being able to re-invent itself over its history, and has faced multiple challenges over the years, so clearly it cannot be written off. But the cost of building chip factories and paying for research and development is prohibitive now in the semiconductor business. Intel needs to make large profits on its existing products in order to finance its future.

Just how Intel can re-invent itself out of the sharp pincers that threaten it is an enigma that I, a dedicated watcher for the last 25 years, cannot fathom myself.